EK-CER researchers from Hungary participate in the NASA Artemis mission

We are entering a new era of human space travel and getting closer to seeing a human walk on the surface of the Moon again. By using the experience gained in these missions, we can make serious progress in achieving a safely feasible human journey to Mars. NASA’s Artemis mission aims to open a new chapter in the field of human space exploration with strong international collaboration; building a novel spacecraft carrying human personnel to the Moon, an orbiting lunar space station, and a base on the surface. As a result of many years of preparation, postponed launches, extended deadlines and budget rethinking, the system that will enable the first lunar test flight of the Orion spacecraft (Exploration Mission-1) is ready. Space radiation measurements are one of the major tasks during the mission in order to understand the potential adverse health effects on future astronauts working in the harsh cosmic environment.

Map of the Artemis I mission with major planned stations (NASA)

A phantom in outer space

When planning human missions, there are a lot of key radiation-related issues that must be carefully studied, such as the understanding of the relationship between skin exposure and the dose absorbed in the internal organs, the design of optimal radiation shielding conditions, and determining appropriate dose limits. Studying the penetration of cosmic rays inside the body is only possible with the help of humanoid mannequins. This is not a new idea: human skull imitations were used in radiation measurements as early as the 1990s on board several space shuttles and in the Mir Space Station.

In the past, EK-CER researchers participated in a series of experiments using a highly detailed phantom made by the German Aeronautics and Space Agency (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt, DLR) sponsored by the European Space Agency (ESA). The soft tissues and lungs of the phantom in the Matroshka program were made of tissue-identical low-density polyurethane and had real human bones. Hundreds of measurement positions were devised inside the body for active (energy-demanding) and passive (post-evaluation) radiation detectors. Between 2004 and 2011, measurements were first performed outside the International Space Station and later inside various modules. It is interesting to note that similar phantoms are used in the testing and calibration of radiotherapy irradiation equipment in healthcare.

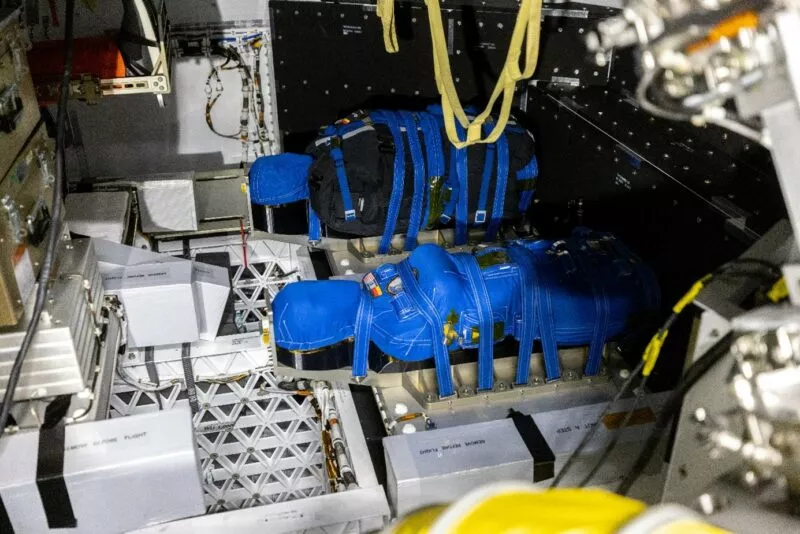

Helga and Zohar are already in the Orion capsule (Photo: ESA/DLR)

The MARE experiment

The Matroshka AstroRad Radiation Experiment (MARE) performed on board the Orion spacecraft will apply humanoid phantoms as well, which are also manufactured by the DLR under an ESA contract. Researchers experienced in phantom measurements are participating in the experiment using dosimeter sets from several countries (Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, the United States and Japan). Similar to the Matroshka missions, the aim is to determine the quantity and quality of ionizing radiation absorbed in different tissue types, thereby assessing the radiation exposure of the crew. An essential difference is that in this case the phantoms imitate the female body. The difference in the tissue distribution and organ structure of the male and female body are significant both biologically and in terms of radiation protection, which means that the new results will be unique. During the mission, two identical phantoms – named Helga and Zohar – will be seated side-by-side, while Zohar will also wear an AstroRad radiation protection vest. The vest has already been tested on board the International Space Station, but the lunar journey creates unique conditions, which should result in useful new information. In addition to the 1,400 sensor positions inside the phantoms, measurements will also be made on the outer surface of the vest in order to assess how much radiation can be avoided when wearing the protective equipment.

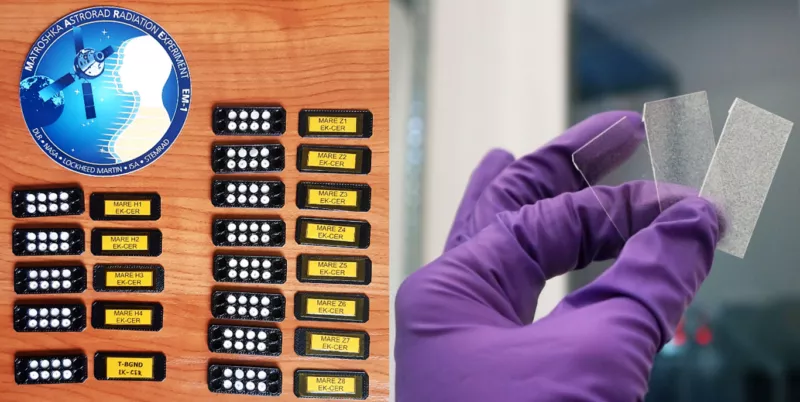

The passive dosimeter sets

There is not a large amount of dosimetry data available from the Apollo missions, so the results of the MARE mission promise to be hugely significant. The participating research teams have been conducting measurements in the Columbus module of the International Space Station for more than ten years as part of the DOSIS-3D experiments. Using the experiences gained in this collaboration, a measurement set-up was developed in which cosmic radiation can be detected simultaneously with different types of passive dosimeters. This sets consisting of thermoluminescent dosimeters and solid-state nuclear track detectors placed on the body surface of phantoms and both below and above the radiation protection vest. On the surface of the solid-state nuclear track detectors, particles with higher energy release (such as protons and atoms that fly at near the speed of light during supernova explosions) cause visible tracks, while thermoluminescent detectors store the information of the particles with lower energy release (gamma radiation, neutrons) that penetrate the spacecraft’s walls. These detectors will be evaluated in the ground facilities at the end of the mission.

Thermoluminscent detectors prepared to the MARE mission in their 3D printed holders (on the left) and solid-state nuclear track detectors irradiated with different doses during calibration tests (on the right) (Photos: EK-CER)

Ready to launch

The Orion spacecraft and the SLS (Space Launch System) rocket are already assembled and waiting for the pre-launch tests to be done. Launch Complex 39B, the iconic site of the Apollo and space shuttle launches, has been renovated and will be the starting point for this historic series of missions.