Alarming Findings: Human Impact on Biodiversity Greater Than Previously Thought

Biodiversity is declining at a dramatic rate. Earth’s biota is changing at an accelerating pace: species numbers are decreasing, and ecological communities are being reshaped – all driven by human activity. A new study, the most comprehensive of its kind to date, has been published in Nature by an international research team including the HUN-REN Balaton Limnological Research Institute (HUN-REN BLRI). The results are startling.

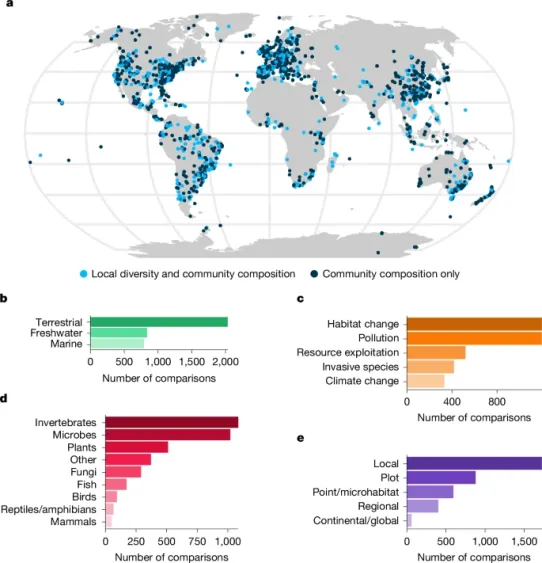

Previous studies on biodiversity loss have often focused on a single location, time period or human pressure. This new global analysis, however – conducted with the involvement of HUN-REN BLRI’s Kálmán Tapolczai – synthesised data from nearly 73,000 published studies on the subject. Of these, more than 2,100 contained data suitable for further analysis. Altogether, the research compared biological communities across approximately 50,000 human-impacted sites and an equal number of relatively undisturbed locations.

The study was not limited to a single taxonomic group or habitat type. It encompassed terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems and included microorganisms, fungi, plants, invertebrates, reptiles, amphibians, fish, birds, and mammals. This broad scope allowed the researchers to examine changes in community structure on a global scale in response to human pressures, with a particular focus on declines in species richness and biotic homogenisation – the process by which communities in impacted areas become more homogeneous and less diverse.

The findings are unequivocal and leave no doubt about humanity’s destructive impact on biodiversity. The researchers examined the five most important negative effects of human activity:

- Land-use change – including deforestation, urbanisation, and the expansion of agriculture

- Resource exploitation – such as overfishing, hunting, and excessive logging

- Climate change – with rapid shifts in climate proving fatal for many species

- Pollution – including chemical contamination, plastic waste, and air and water pollution

- Invasive species – non-native organisms introduced by humans that displace native species

The study clearly demonstrates that these pressures negatively affect all major taxonomic groups and ecosystems worldwide.

Source: Keck et al., The global human impact on biodiversity. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08752-2. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The results are striking: across all human-impacted sites, species richness is on average 20% lower than in relatively undisturbed areas. Locally, the greatest losses have occurred among vertebrates – particularly amphibians, reptiles, and mammals – which are more vulnerable to extinction due to their smaller population sizes. But it is not only the number of species that is declining: human pressures are also radically altering the composition of communities within habitats. In mountainous regions, for example, climate change may allow plant species from lower elevations to outcompete those adapted to higher altitudes, while some species may disappear from certain areas altogether.

The study found particularly pronounced shifts in community composition among microorganisms and fungi, while changes were less marked among mammals, fish, reptiles, and amphibians. These findings support theories suggesting that smaller-bodied organisms – which typically exhibit higher species richness, shorter life cycles, and greater dispersal ability – respond more rapidly to environmental change and display more substantial shifts at the community level. Crucially, the loss of key species from ecosystems can have serious consequences for the overall functioning of the system.

Beyond its scientific findings, the study also serves as a call to action. Biodiversity loss is not merely about the disappearance of species; it represents the transformation of entire ecosystems, undermining their functioning and the ecosystem services upon which modern human civilisation depends. The paper therefore urges policymakers to take urgent and decisive measures to safeguard biodiversity.

Co-author Kálmán Tapolczai has previously investigated the responses of microbial communities – particularly algae – to human pressures, as these organisms are strong indicators of environmental change. In Hungary, Lake Balaton is especially affected by the anthropogenic pressures analysed in the study, including factors that contribute to algal blooms, the impact of urbanisation on biological communities, and the presence of invasive species. Researchers at HUN-REN BLRI have long been studying these phenomena. This latest study places their research in a global context and underscores the importance of long-term ecological monitoring programmes, which provide the foundation for large-scale analyses and the practices informed by them.