Only Active Where it’s Needed: HUN-REN RCNS Researchers are Developing a New Kind of Targeted Cancer Therapy

In their latest study, researchers from the MTA-HUN-REN TTK Lendület (Momentum) Chemical Biology Research Group at the Institute of Organic Chemistry of the HUN-REN Research Centre for Natural Sciences (HUN-REN RCNS) have devised a strategy to improve the precision of chemotherapy drugs by enabling their active compounds to be triggered more accurately in both space and time. The results were published in one of the most prestigious chemistry journals, the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

One of the biggest advantages of targeted chemotherapy is that the active compounds work mainly in cancer cells, causing fewer harmful side effects in healthy tissues. But it’s not only about getting the drug to the right place, it also matters when and under what conditions it becomes active. Ideally, the researchers say, the compound would “switch on” only near the tumor, triggered by some external or internal control.

One way to achieve this is to activate drugs with light, for instance by using light-sensitive blocking or protective groups. These light-responsive (photolabile) protective groups make it possible to control a drug’s activity in both space and time using light. However, light can only be targeted with real precision when the target area is clearly defined and sharply bounded.

If cancer cells are scattered, for example, extra control elements are needed so that light activation truly happens only in the tumor’s immediate environment, and not in healthy cells, the researchers explain. At the moment, however, there are only a few approaches that can tie photolabile-group activation to additional conditions in this way.

Researchers at the MTA–HUN-REN TTK Lendület (Momentum) Chemical Biology Research Group of the HUN-REN Research Centre for Natural Sciences have developed a new approach that works like two-step authentication, using two separate “safety checks” to activate a drug compound.

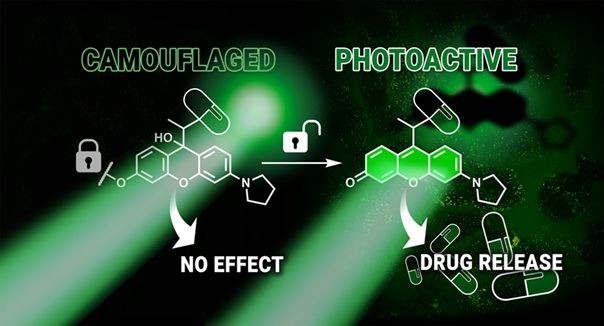

They created a photolabile protective group that is colorless in its default state, meaning it does not release the active ingredient even when exposed to light. This “camouflaged” state can be removed through a biocompatible, selective so-called bioorthogonal reaction. After that reaction, light irradiation can finally trigger the linked, previously inactive compound to detach and become active.

If the chemical reaction that removes the “camouflage” takes place only on the surface of cancer cells or inside them, then light exposure will enable activation only there and not in healthy cells. The researchers confirmed the concept in cell-based experiments: the potent topoisomerase inhibitor SN38 was released only when both conditions were met, meaning the chemical reaction occurred and the cells were also irradiated with green light.

explained Dr. Péter Kele, head of the research group.

Although more research is still needed before this can be used clinically, the results point to a new direction in light-controlled drug activation. In the long run, the discovery could support the development of methods that allow drugs to be switched on with high precision and minimal side effects.