Hungarian Research Shows That Trees Over 100 Years Old Are Far More Effective in Combating Warming Than Previously Thought

Hungarian researchers participated in a unique pan-European study showing that Europe's forests could sequester up to 309 megatonnes of carbon dioxide annually if allowed to revert to their natural state. In theory, this could neutralise a significant proportion of the CO2 emissions from European passenger cars.

The European Environment Agency (EEA) estimates that in 2022, vehicles in the European Union emitted around 800 megatonnes of carbon dioxide, with passenger cars contributing approximately 480 megatonnes. The recent publication is particularly intriguing in light of these figures, as it suggests that researchers have previously underestimated the carbon sequestration potential of Europe’s primary and old-growth forests.

"Unfortunately, land use in Europe and globally has been driven by deforestation for many centuries, from the vast amounts of timber felled to build medieval ships to meet the raw material demands of the Industrial Revolution. By the 1800s, more people began to recognise the rapid disappearance of true primary forests, but their protection only became a priority when very few remained. Today, researchers are particularly interested in understanding the unique and rare ecosystems, self-regulating systems, and dynamics of these forests. A key question in this context is how much carbon a natural forest can sequester over the long term," said Ferenc Horváth, a member of the Forest Ecology Research Group at the HUN-REN Centre for Ecological Research, who participated in the study, in response to a question from the HUN-REN portal.

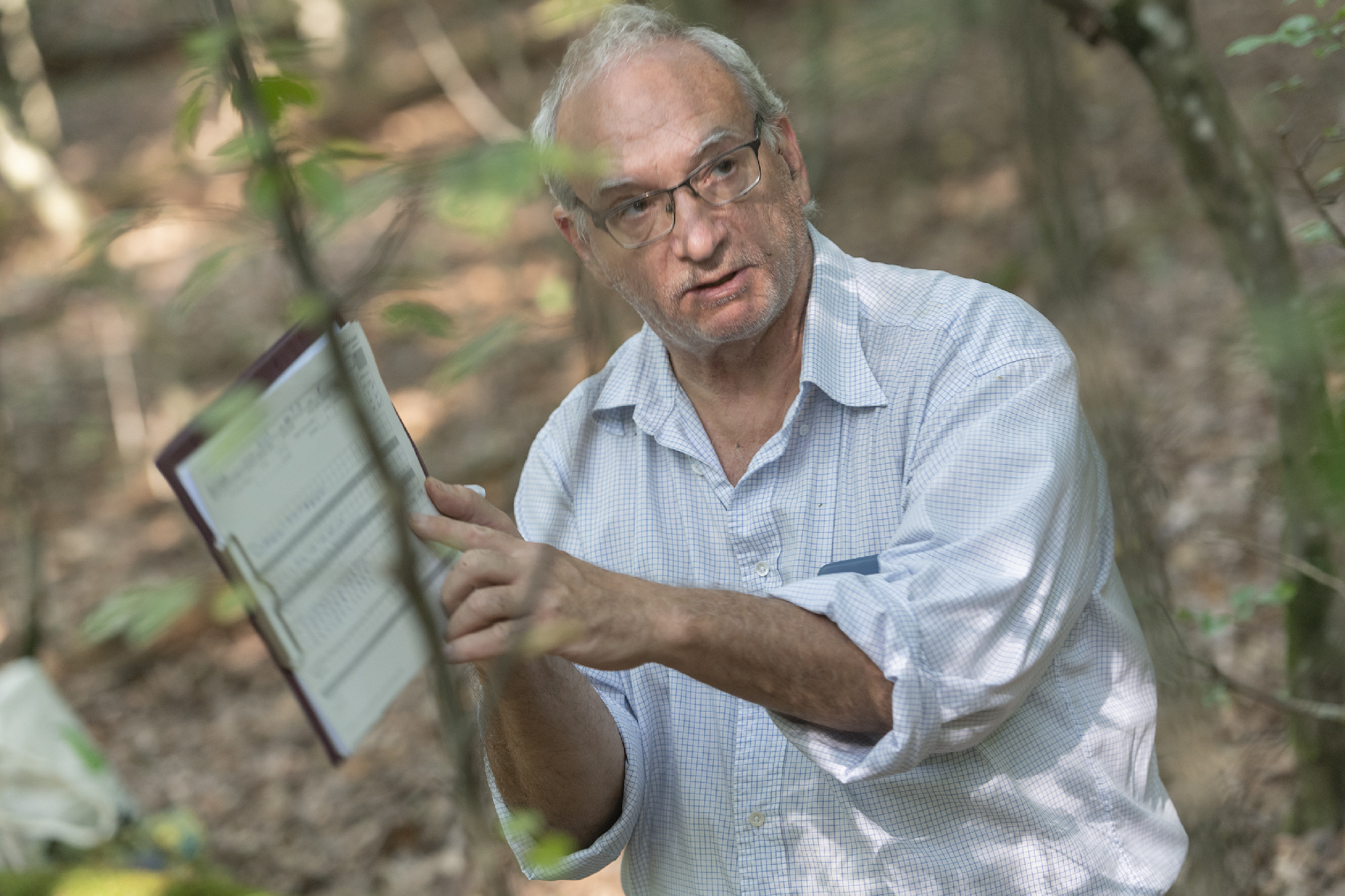

Hungarian researchers, led by Ferenc Horváth, played a crucial role in collecting data on the continental zone. Photo: Márton Kovács

Photo: Marton_KOVACS

The study, published in Nature's prestigious journal Communications Earth & Environment, examined over 288,000 trees across nearly 8,000 sites in 27 countries, calculating the carbon stored in above-ground, below-ground, and dead biomass. This analysis provided reference values for different forest types and ecological zones, revealing, for instance, that alpine birch forests in the north sequester the least carbon, while mixed spruce-fir-beech forests in the Balkans capture the most. The study also estimates that European forests could potentially sequester up to 309 megatonnes of carbon dioxide annually over a 150-year period if left to grow and revert to their natural state without further exploitation. Hungarian researchers, led by Ferenc Horváth, played a crucial role in collecting data on the continental zone. They surveyed nearly 600 sample sites, ranging from 130–170-year-old lowland stands to 160–200-year-old trees on Kékes Mountain and the extensive oak forests in Transcarpathia. A key finding of the study is that trees with trunks over 60 centimetres in diameter store significantly more carbon than smaller trees, yet forest management practices often involve harvesting trees before they reach this size.

The primary forest remnant on Kékes Mountain is the oldest forest in Hungary. Photo: Tamás Vig, 2021

The study aims to make European decision-makers aware that if we stop felling trees at half their lifespan and instead allow them to mature, they could sequester unprecedented amounts of carbon, significantly helping humanity's fight against climate change.