Similar Rituals, Divergent Kinship Systems in Copper Age Communities of the Great Hungarian Plain

An international research team has demonstrated the genetic continuity of populations in the Great Hungarian Plain at the dawn of the Copper Age — a period marked by profound cultural and social transformation. Through advanced genetic analysis, the researchers revealed that communities residing in close proximity and sharing comparable material cultures and burial rites were organised according to fundamentally different kinship systems during the second half of the 5th millennium BCE. The study also identified frequent cousin marriages at one of the Plain’s archaeological sites. The research, led by Anna Szécsényi-Nagy (Institute of Archaeogenomics, HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities) and Zsuzsanna Siklósi (MTA–ELTE Momentum Innovation Research Group), was published in Nature Communications.

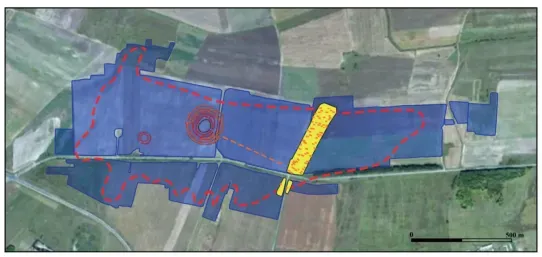

According to archaeological research, the mid-5th millennium BCE saw a period of radical transformation across all aspects of life in the Great Hungarian Plain. Over the course of roughly 150 years, the region’s inhabitants abandoned the Neolithic settlement mounds — known as 'tells' — along with their vast settlements, which covered up to 60–80 hectares and, according to demographic estimates, may have housed several thousand people. By the beginning of the Copper Age, these had been replaced by a dense network of small, farmstead-like settlements comprising just a few houses. This shift was accompanied by changes in material culture and, for the first time in the region’s history, by the emergence of cemeteries that were physically separate from settlements.

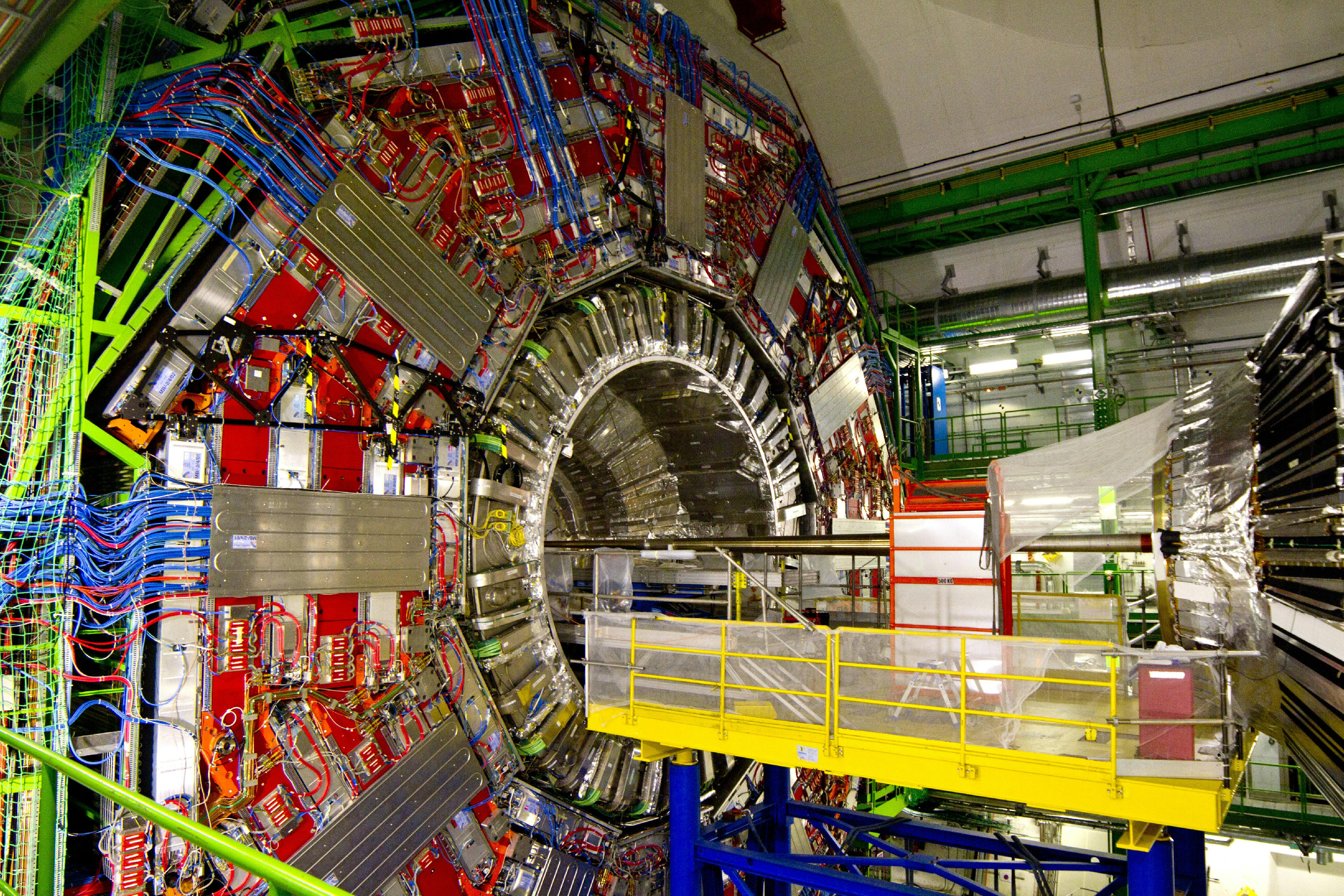

Map of the Neolithic settlement at Polgár-Csőszhalom (adapted from Mesterházy et al. 2019, Fig. 7)

An international research team led by Hungarian scholars set out to determine whether the transformations associated with the onset of the Copper Age were driven by the arrival of new populations or by continuity within local communities. They also examined how the newly established Copper Age cemeteries were organised, what kinds of kinship ties existed between individuals buried next to one another, and whether there were structural differences between the organisation and kinship systems of Neolithic and Copper Age communities.

At the Neolithic site of Polgár-Csőszhalom and the nearby Copper Age cemetery of Tiszapolgár-Basatanya, both located in the Polgár region by the River Tisza, researchers combined population genetics, genetic kinship analysis, and methods for detecting more distant genetic relatedness with archaeological and anthropological observations. The Basatanya cemetery was also compared with the contemporaneous Copper Age cemetery of Urziceni-Vamă, situated near the present-day Hungarian–Romanian border.

‘By examining individuals who once lived near Polgár, on the banks of the River Tisza, we identified clear biological continuity between the Late Neolithic and Early Copper Age populations,’ said Anna Szécsényi-Nagy, Director of the HUN-REN RCH Institute of Archaeogenomics, highlighting one of the study’s key findings. This result lends support to the archaeological interpretation that, although local society underwent radical change during the transitional period between 4500 and 4350 BCE, there is no evidence of new populations arriving from elsewhere.

Late Neolithic burials from Polgár-Csőszhalom (1–2) and Early Copper Age burials from Tiszapolgár-Basatanya (3–6)

(adapted from Raczky et al. 2014, Fig. 5)

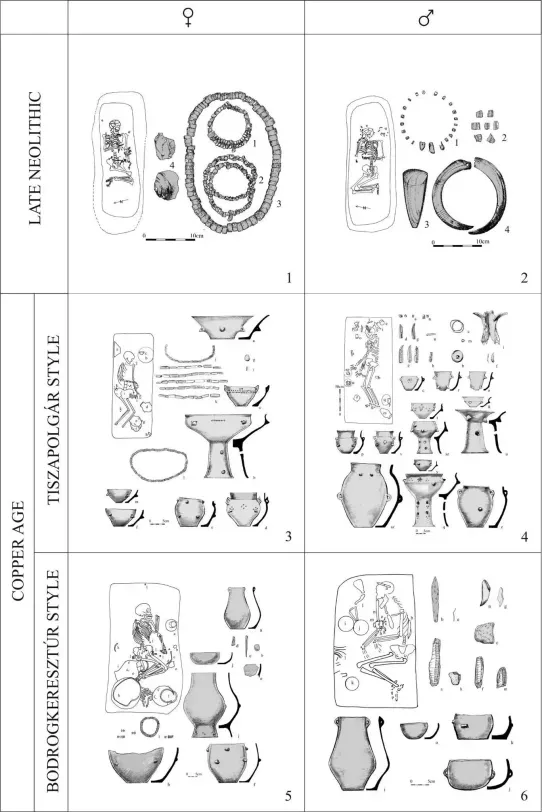

‘The Tiszapolgár-Basatanya site from the Early Copper Age (4350–4000 BCE) is a fascinating area of research for several reasons. Until now, little was known about the biological relationships between individuals associated with different material styles, or about mate selection and burial placement preferences within the cemetery community,’ emphasised Zsuzsanna Siklósi, head of the MTA–ELTE Momentum Innovation Research Group. The recently published study demonstrated that individuals associated with different ceramic styles were biologically related. The Tiszapolgár-Basatanya cemetery was formed by a biologically closed community whose members were likely socially and culturally isolated from their contemporaries — as indicated by the frequent occurrence of close-kin marriages, most likely cousin unions.

Biological kinship network and reconstructed family trees from Tiszapolgár-Basatanya

At Basatanya, families followed a patrilineal system of descent. After marriage, men remained in their childhood homes, and the burial places of their ancestors remained significant for several generations. Close relatives were buried directly next to or near one another. In this sense, they preserved local Neolithic traditions: at Csőszhalom, too, close kin were buried side by side within the settlement itself — although that community was likely much larger in terms of population.

Early Copper Age burial from the Urziceni-Vamă site

Although further sites in the region need to be analysed in similar depth to draw conclusions on a historical scale, certain patterns are already becoming apparent. Genetic kinship networks have revealed that, despite sharing similar material cultures and burial rites, Early Copper Age communities of the Great Hungarian Plain were organised according to markedly different systems. A strikingly different structure was identified at the contemporaneous Urziceni-Vamă cemetery, located just 100 kilometres from the Polgár region. Here, fathers were notably absent from smaller family units, and close relatives were buried far apart within the cemetery. The absence of close-kin marriages and the presence of a wide-ranging genetic network suggest that the Urziceni cemetery may have been used by a community up to six times larger than that at Basatanya.

Biological kinship network and reconstructed family trees from Urziceni-Vamă

These findings are an important reminder that the social organisation and kinship practices of prehistoric communities could vary considerably — even among contemporaneous groups living in close proximity and sharing similar material cultures. Therefore, excessive generalisations can be overly simplistic and potentially misleading.

To lay the foundations for the study, archaeologists and anthropologists from Eötvös Loránd University — Alexandra Anders, Pál Raczky, and Zsuzsanna Siklósi (Institute of Archaeological Sciences), and Tamás Hajdu (Institute of Biology) — together with the Department of Anthropology at the Hungarian Natural History Museum (Sándor Évinger and Tamás Keszi), the Budapest History Museum (Zsuzsanna M. Virág), and the Satu Mare County Museum (Cristian Virag), initiated a collaboration with the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology at the University of Vienna (Ron Pinhasi) and the laboratory at Harvard Medical School (David Reich), where the human DNA samples were extracted. The genetic data were analysed under the leadership of Anna Szécsényi-Nagy at the HUN-REN RCH Institute of Archaeogenomics.