Breakthrough discoveries by HUN-REN researchers on cancer immunotherapy side effects through large-scale bioinformatic data analysis

A paper examining the side effects of cancer immunotherapy, with Csaba Kerepesi, a researcher at the HUN-REN Institute for Computer Science and Control (HUN-REN SZTAKI) as the first author, was published in a subjournal of the prestigious Journal of Clinical Oncology. The researchers found that the greater the difference between cancer cells and healthy cells, the stronger the autoimmune side effects of the therapy are, whereby the immune system also attacks healthy cells. The results validated the new immune theory developed in 2007 by Tibor Bakács (HUN-REN Rényi Institute) and colleagues, and could aid in more effectively predicting the side effects of immunotherapy, as well as in enhancing the treatment's efficacy, which may one day offer a solution against most types of cancer.

Unfortunately, deactivating these inhibitory mechanisms can result in widespread autoimmune side effects. Reports, including those by The New York Times, have highlighted that inhibiting these checkpoints activates the immune system against not only the tumours but also essential healthy organs. Such autoimmune reactions can significantly impair a patient's quality of life, sometimes requiring halting the therapy. Enhancing the understanding of these side effects' underlying processes could significantly contribute to improving the safety and efficacy of the treatment.

In a previous paper, Csaba Kerepesi, along with Tibor Bakács and colleagues, demonstrated that the autoimmune side effects suring immunotherapy are more common in tumours with a higher number of mutations. In the current study, the two researchers, in collaboration with partners from the US (such as the Yale University, Harvard University, and University of Oklahoma), further investigated the relationship between the tumour microenvironment and the side effects of immunotherapy.

Csaba Kerepesi analysed more than 10 million reports collected in the Adverse Event Reporting System operated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA FAERS) including the data of 58,961 patients who were treated with checkpoint inhibitor drugs. He processed these patients' data, along with that of the so-called Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), using bioinformatics methods, conducting correlation analyses on 33 types of cancer. According to the results obtained, the occurrence of autoimmune side effects was most common in melanoma and lung cancer. These tumours contain the highest number of new antigens induced by mutations.

The results confirmed the new immune theory

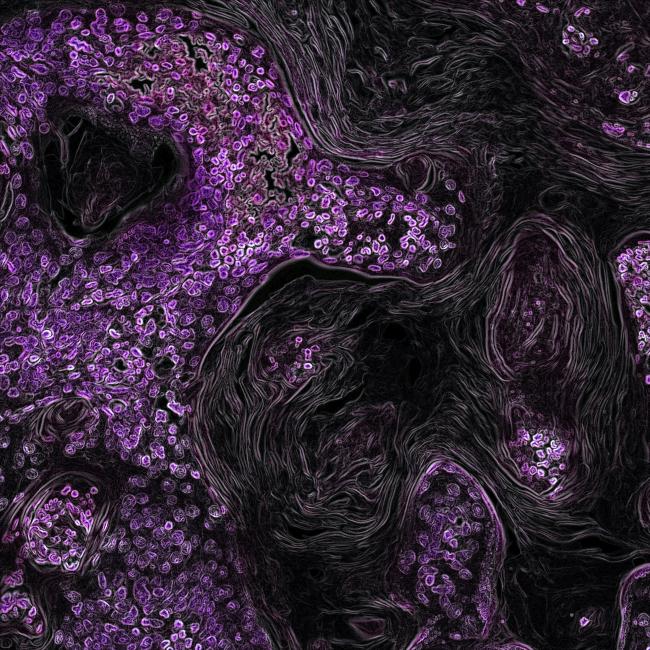

The paper published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, the scientific journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), within the Precision Oncology section, revealed that the occurrence of autoimmune side effects during cancer immunotherapy is related to the tumour’s immune microenvironment. This is especially true for new antigens produced during tumour mutations and the number of CD8+ T-cells infiltrating the tumour. An essential function of T-cells is to recognise and destroy foreign cells, such as those cancerously mutated or infected, distinguished by these new antigens. Therefore, the findings indicate that the more cancer cells differ from healthy cells, the stronger the autoimmune side effects of cancer immunotherapy, leading the immune system to also attack healthy cells. These results could aid in more accurately predicting the side effects of immunotherapy and enhancing the therapy's effectiveness, potentially offering a solution against most cancer types. Contributors to the study include researchers from Semmelweis University in Hungary, Harvard, Yale, and the University of Oklahoma, among others.

The results of the new study confirmed the new immune theory developed by Tibor Bakács and colleagues in 2007. According to the previous consensus, the immune system evolved primarily to combat infections. In contrast, the Hungarian immune theory proposed that evolutionary pressure was focused on controlling mutations that induce cancer cells. The new model more realistically explained how a complex system could be overseen by a system of inspectors who are only familiar with a fraction of what they need to monitor. According to this theory, the immune system only needs to recognise its own cells to attack foreign ones (cancerously mutated or infected). These foreign cells are distinguished from the body's own cells by new antigens.

The results of this study also support the key hypothesis of Bakács and colleagues' theory, which suggests that the immune system continuously monitors its own cells. Therefore, the medicinal deactivation of immune checkpoint inhibitors not only enhances the destruction of tumour cells but also damages healthy tissues in the process. Consequently, the medical challenge lies not in suppressing the autoimmune reactions responsible for tumour destruction with steroid drugs, but in taming them through the application of low-dose therapy.