How the Wells Supplying Clean Drinking Water to Over 1.5 Million People Around Budapest Actually Work

Where does Budapest’s clean drinking water come from, and how does it reach households? A recent research project involving several HUN-REN institutes, the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, the University of Miskolc, the National Public Health Centre, and the Budapest Waterworks Company is shedding light on this vital question.

Led by the HUN-REN Centre for Ecological Research and involving researchers from several other HUN-REN institutes—including György Czuppon, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Geological and Geochemical Research (FGI) of the HUN-REN Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences—this multidisciplinary study aimed to determine how long it takes for Danube water to reach high-capacity collector wells. It also sought to assess the proportion of background water—that is, groundwater—relative to Danube water in production wells supplying drinking water, as well as water for

The researchers emphasise that riverbank filtration plays a crucial role in the global supply of drinking water. In this natural process—known as bank filtration—Danube water seeps through layers along the riverbank and is naturally purified before reaching the wells used for drinking water abstraction. According to a study published in the Journal of Hydrology, this purification takes place as the water passes through gravelly riverbed deposits—a process that is, however, highly vulnerable to contamination. Flooding or pollution in the river can affect the system’s efficiency, which is why the researchers conducted year-round monitoring of the physical and chemical characteristics of both Danube water and well water on Szentendre and Csepel Islands.

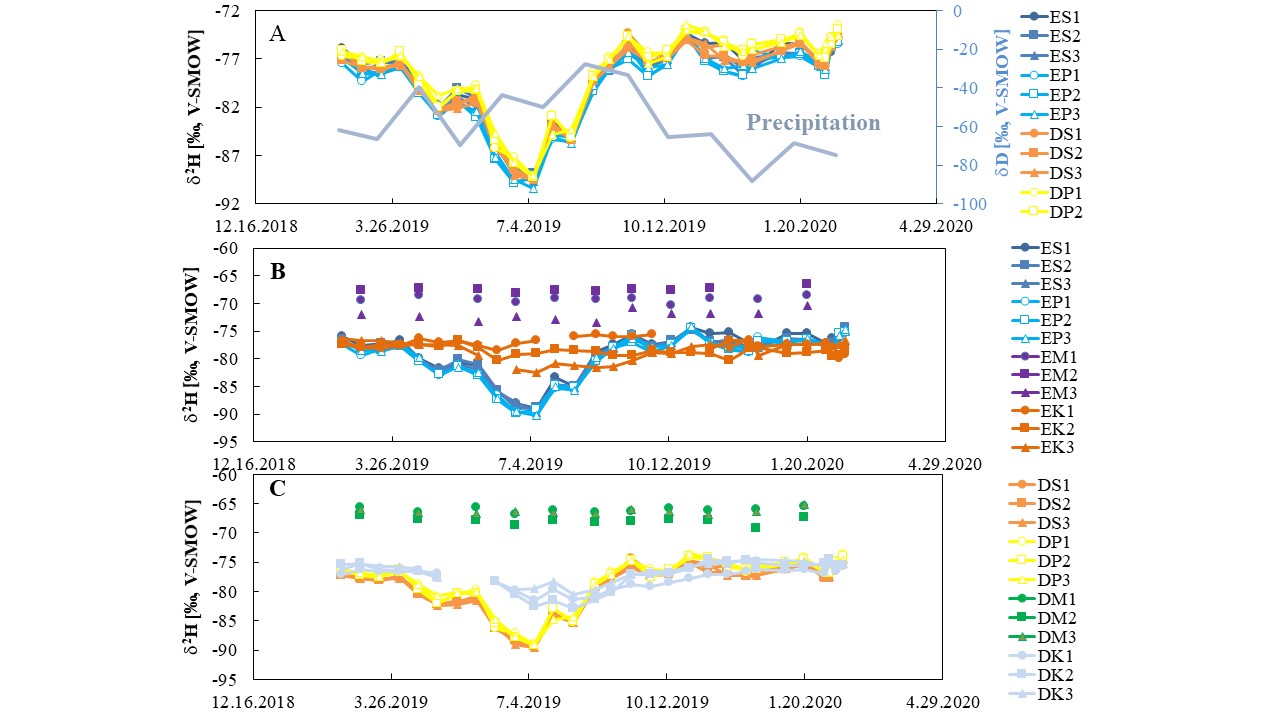

Stable isotope time series of the Danube at Surány (ES1–3: mid-river; EP1–3: near the riverbank) and Ráckeve (DS1–3: mid-river; DP1–3: near the riverbank) (A); observation (EM1–3) and production (EK1–3) wells in the Surány area (B); and observation (DM1–3) and production (DK1–3) wells in the Ráckeve area (C).

As part of the study, the researchers found that it typically takes Danube water between two and seven weeks to reach the wells, depending on the distance from the river and the structure of the subsurface layers. However, this process can accelerate significantly during flood events, when river water may reach the wells in just a few days.

The Danube in Budapest is no longer quite the same river as it is in Vienna – and that’s perfectly natural

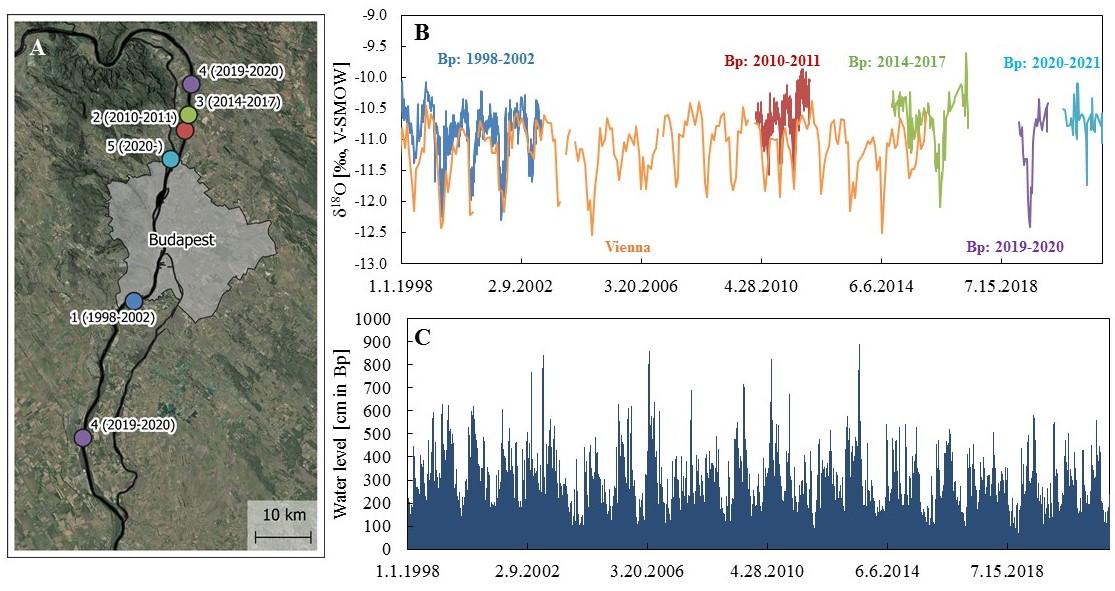

Based on an analysis of two decades' worth of data, the team found that the isotopic composition of the Danube near Budapest differs slightly from that observed further upstream in Vienna. This is primarily due to the influence of local groundwater and, to a lesser extent, evaporation.

Location of sampling sites along the Danube (A). Oxygen isotope composition of the Danube in the Budapest area (B) (blue: 1998–2002; red: 2010–2011; green: 2014–2017; purple: 2019–2020; light blue: 2020–present). The orange curve shows the δ¹⁸O values of the Danube in Vienna (IAEA GNIR database; Rank et al., 2012, 2018). Water levels measured in Budapest between 1998 and 2021 (C).

“There is a systematic difference in the hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratios between the Danube in Vienna and the Danube in Budapest. In other words, the Danube near Budapest contains a higher proportion of the heavier stable isotopes,” explained György Czuppon. “This suggests that, by the time the river reaches Budapest, slight evaporation has occurred, and the contribution of smaller streams, rivers, and groundwater between the two cities has also shifted the isotopic composition to some extent. I should stress that this is neither good nor bad in terms of drinking water quality.”

Overall, the study emphasises the vital importance of this type of research in ensuring that Budapest’s residents continue to have access to safe, naturally sourced drinking water. The experts also recommend conducting similar investigations at other wells, particularly those with the highest yields.

These findings could support cities around the world that rely on riverbank filtration for their drinking water.